Our job as a software publisher is to listen to our users’ expectations and enhance our product to meet them.

Being open source is what makes BlueMind unique. Yet openness can sometimes be detrimental to its development.

As a result of our product’s success, we’ve had enormous amounts technical and functional feedback and we’ve had to organise ourselves in order to process it.

Business model

Before moving on to the thick of things, we should explain what our job as a software publisher means, our business model and its impact on our organisation.

As software publishers, we focus on software development, product enhancement and technological partnerships. Our target market isn’t country or business-specific. Today, everyone needs email, and BlueMind responds to this need whether you are an SME or a multinational corporation.

To achieve global coverage, we work with a distribution network made up of partners who implement the projects for our clients and/or set up SAAS platforms.

Our network of partners enables us reach a must greater number of potential clients.

This has two consequences:

- most clients come through our partners, which means we don’t know all of them

- our number of clients is going to keep growing

As a result, we must set up a series of tools and methods to collect our clients’ feedback and requests in order to process them as best we can.

Organising Development

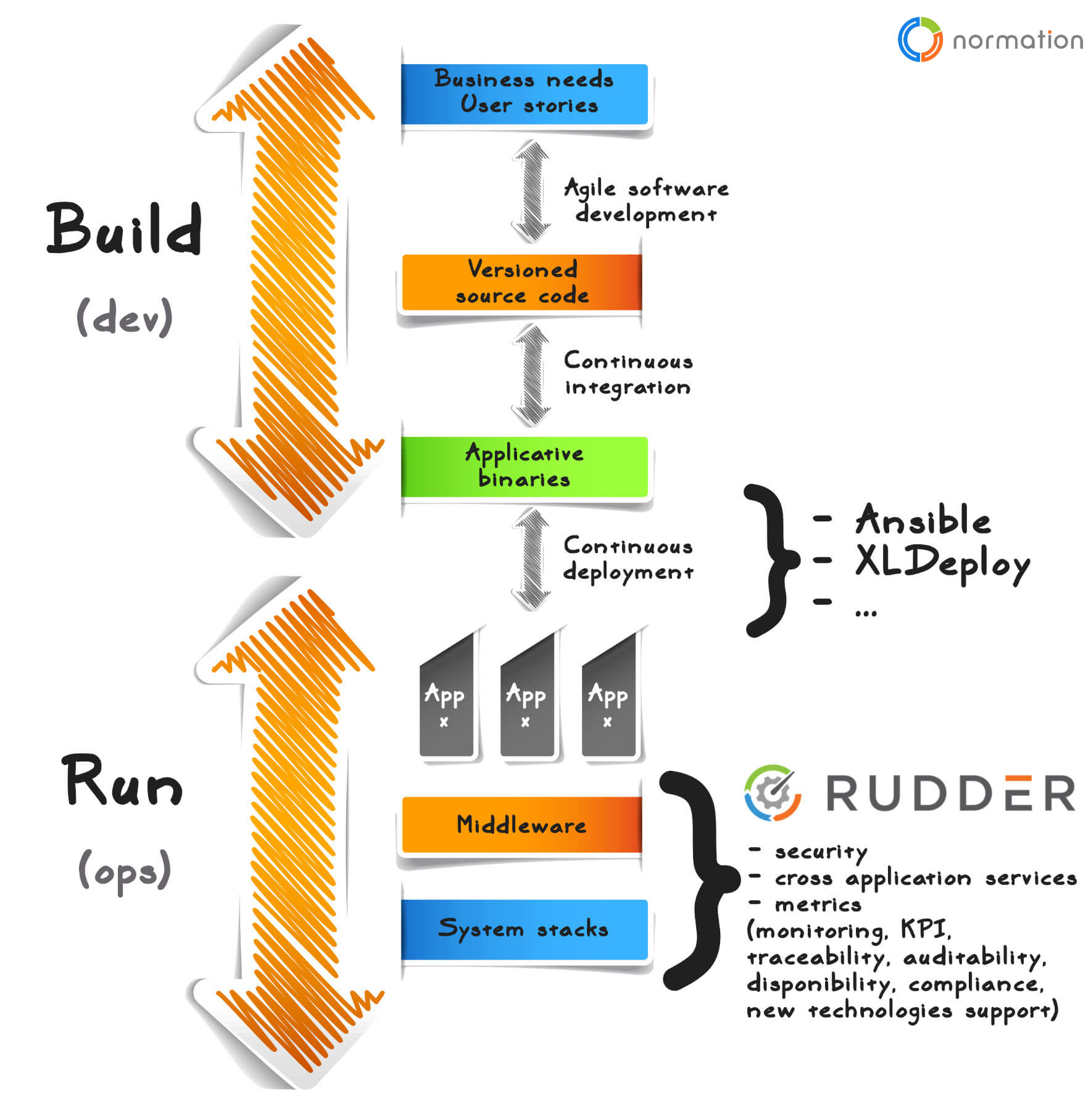

In the DevOps sense, as shown in this chart by our Normation colleagues, in the process from application development to production implementation, two parts are involved: BUILD and RUN.

In the DevOps sense, as shown in this chart by our Normation colleagues, in the process from application development to production implementation, two parts are involved: BUILD and RUN.

The job of a software publisher is to BUILD, i.e. to take business requirements to create “application binaries”. In the Agile sense, business requirements can take different forms (stories, epics, etc.)

BlueMind’s R&D team has been using agile methods since the product’s early days. This has allowed us to develop features quickly, within a specific context. A whole series of automations and tests allow us to deliver new versions with new features quickly.

This article looks at the issue of handling large amounts of business requirements: how can we process them and incorporate them into our R&D appropriately?

Managing business requirements

Why manage them? People ask for things and we do them!

If only things were that simple. We’d need endless resources and all requests would have to be consistent, among themselves and with our vision. In the meantime, we have had to sort through requests and select them to feed a roadmap with a set of features that go into a Backlog.

The backlog contains a number of features which have to be sorted through and validated by a Product Owner. The features at the top of the backlog are processed by our R&D team first.

A simple qualification process

We had set up the following simple and comprehensive feature qualification process (as the young Padawans we were!).

- Understand the request

- Validate or reject the request

- Search for duplicates (who knows whether other users may have made the exact – or not so exact – same request!)

- Create a story for the backlog

- Place it in the backlog according to its priority status set by the Product Owner

- Link it to an Epic, if the story is too big

In theory, this process had 6 steps “only”.

This seems straightforward enough, but it becomes infinitely more complicated when you’re dealing with a large inflow of requests (entered by people who must be clients, but whom you don’t know, much less do you know their vocabulary and their expectations which tend to be too vague). As a result, your backlog becomes, well, backlogged. Looking for duplicates can be time consuming when you’re dealing with a hundred features or so.

In our case, requests come from various sources:

- end clients

- our partners

- internally (developers, sales people, pre-sales people, etc.)

- the software user community

This adds up to huge amounts of people potentially sending feedback and requests.

Most people believe that their requirements are generic, but in most cases they aren’t. Requests aren’t always expressed in the most straightforward manner and everyone thinks their feature is indispensable to their everyday software uses!

Our backlog: on hold

As at January 2015, this was our backlog’s status:

- 140 features not sorted

- 470 stories in the backlog

Among these stories:

- some were important (implementation of a major, structuring feature)

- others were less important (e.g. evolution of an existing feature)

- others were small but legitimate (being able to sort by column: feasible, interesting, but high-priority?)

- others were irrelevant, and possibly clutter (with all due respect to our users “the button would be better in yellow”)

The main issue isn’t so much the flow of feature requests but rather the way they were created and we processed them.

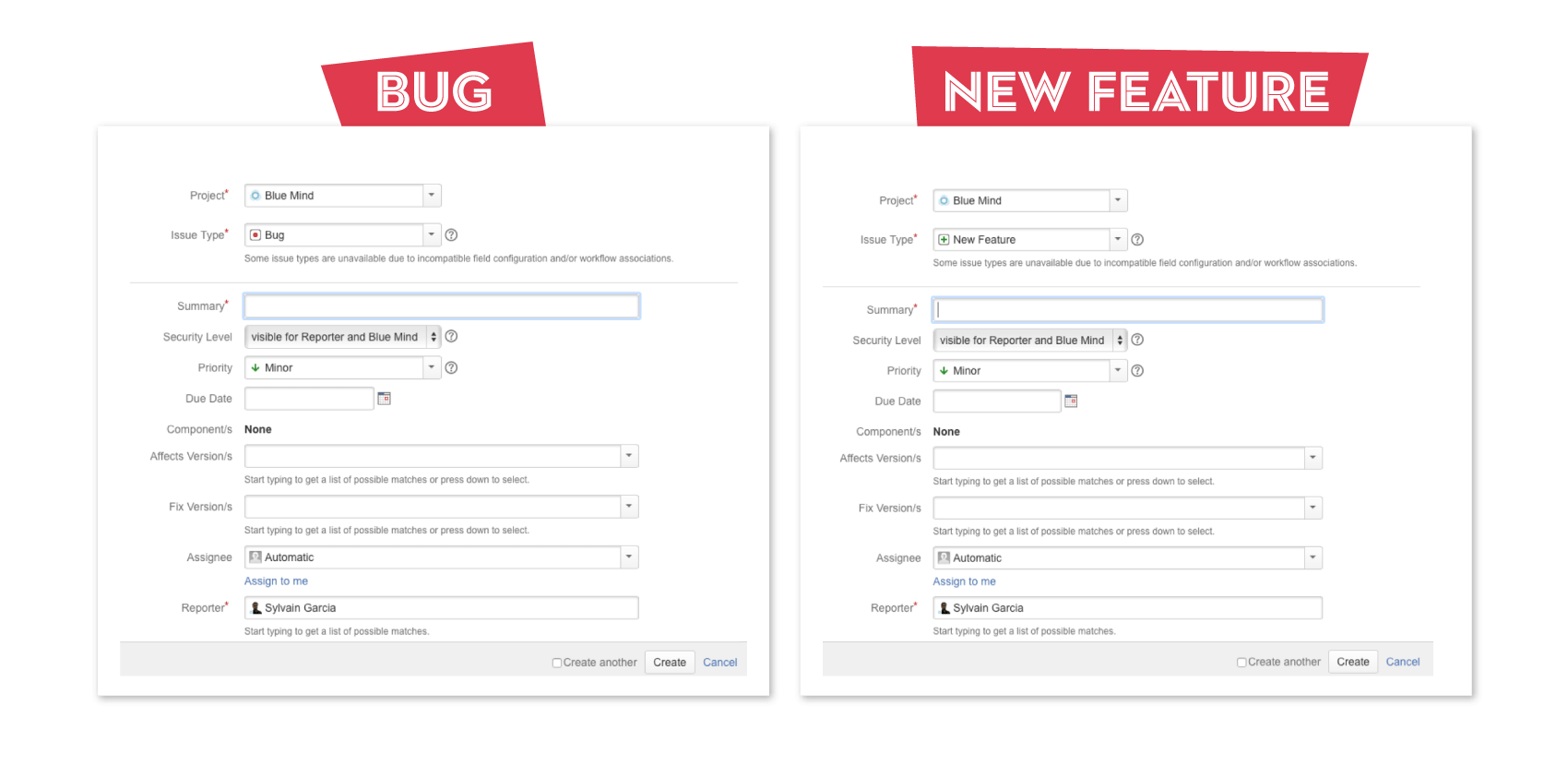

As for all IT projects, we’d set up a bug tracker. In most bug trackers — if not all, as far as we know –, bugs and features are essentially processed in the same way (by default). Typically, the request form is almost identical and a drop-down menu allows users to set the request as “issue”, “bug” or “new feature”.

This is where the trouble is: a bug isn’t a feature! They are two distinct processes with different objectives!

Unfortunately, in bug trackers, the difference between a bug and a feature isn’t clear enough.

A feature ends up having the same level of time constraint — and possibly requirement — as a bug, which shouldn’t be the case.

A bug:

- must have a resolution time-frame and depending on the type of service offered, must follow an SLA

- must be corrected. It is a fault that must be entered into a correction cycle.

- a specific workflow must follow its progress (open, pending feedback, corrected, deployed, “won’t fix”, etc.)

- is critical

- significantly impacts users, who must be informed of its progress.

A feature:

- is a request for an enhancement

- does not have a deadline (contractually)

- is not critical (contractually)

- does not require feedback to users

- can be considered and accepted… or not

This means that by nature, bugs and features are processed in a dramatically different way.

The Suggestion Box

This is why we’ve decided to work differently, to reconsider how we handle features completely. First, we won’t call them “new features” or functionalities, from now on we’ll call them suggestions.

As a result of our analysis, we’ve concluded that to optimise how “suggestion requests” are processed, it is important for the requirement to be described as well as possible by the submitters themselves.

This isn’t a technical issue! But how can we get submitters to be more proactive? The vocabulary we use is important, and it is a first step in conditioning users:

- users will “suggest” rather than “request”!

- “I want” becomes “I suggest that”, “at some point, I’d like”

This is how the Suggestion Box was created. This dedicated UI is principally designed to browse through existing suggestions.

Credit and discipline

The Suggestion Box must encourage users to ask themselves several questions before they submit their suggestion:

Functional questions:

- What is the use of my proposed feature and what will it do?

- What will be its impacts on the BlueMind software as a whole?

Planning questions:

- Has another user already made this suggestion?

- Is there a similar existing suggestion?

If a suggestion can be created immediately, it doesn’t encourage users to think about their expectations. Therefore, each requirement turns into a request, with no prior analysis. And it will have to be analysed before the feature is turned into a story (how it is broken down).

This is exactly what used to happen when we allowed the creation of a “new feature” in our bug tracker: “all I have to do is select from a drop-down list and fill in a title”…

We must therefore guide our users through the process, via a suggestion self-service: the Suggestion Box!

Comment

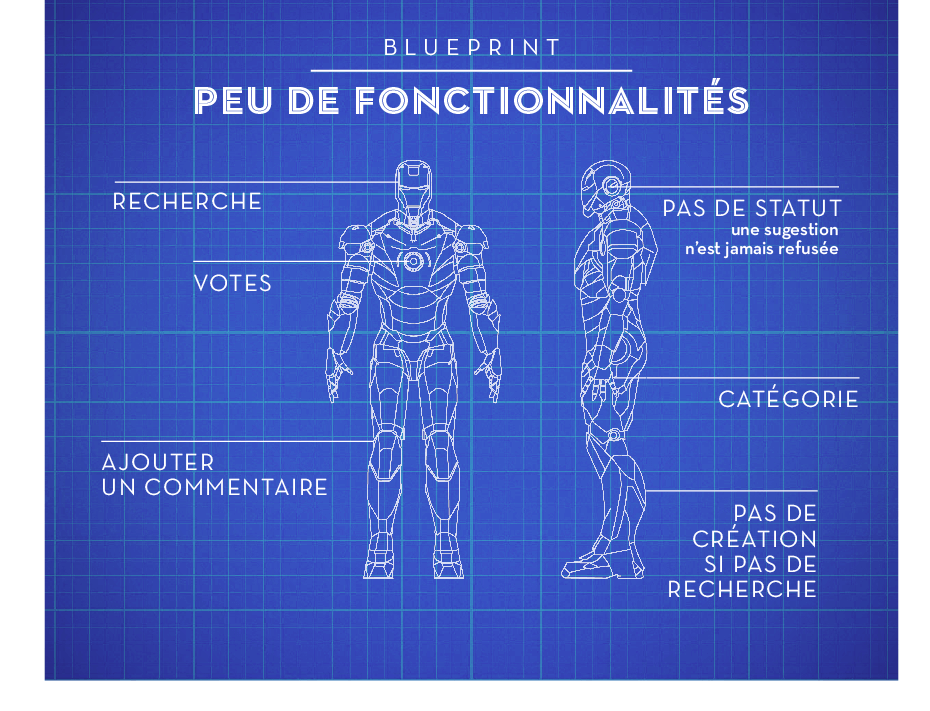

The Suggestion Box was created with the following specifications which are deliberately basic in order to keep the procedure simple:

- Search

The search is important as the UI’s purpose is to go through existing suggestions. We therefore need a powerful search tool.

- Suggestion not created if no prior search

To encourage users to search for a similar request, suggestions cannot be created from the home page. A suggestion can be added only if a search doesn’t produce any relevant results.

- Category

Still in an attempt to get as much information as possible, suggestions must be categorised to help group requests logically and facilitate searches.

- Votes

Votes are designed to help rank requests. They will help identify the most popular requests.

- Comments

If a request is similar to an existing suggestion, comments allow users to give another view on the suggestion and provide new arguments rather than create a new one. Adding to existing demands rather than creating a new one is more useful and it allows a suggestion to collect more votes.

- No status

The point is to allow suggestions to evolve with the community of users and let them become more specific, better-defined and respond to the expectations of as many people as possible. Anyone can add a comment and enhance their vision at any time. BlueMind takes it over at the appropriate time and sets it as “accepted” to draw up the final specifications and carry out the suggestion.

How does BlueMind use the Suggestion Box?

Designing a software RoadMap is a publisher’s job. The Suggestion Box is a component that contributes to the RoadMap among many others. The Suggestion Box is not the absolute basis for the RoadMap, but it will serve to complement the feedback and planned internal projects.

The number of votes for a suggestion tells us how popular a request is. However, BlueMind may decide not to give priority to a suggestion with a large number of votes and prefer a less popular suggestion.

This is because for technical, planning, consistency or strategic reasons, the Product Owner is the one who makes the final decision on a sprint R&D.

Moreover, “internal” tasks, not requested by users (change in API, development library, etc.) may be given priority in order to plan for the possible development of an advanced feature at a later time.

When we decide to upgrade a component (calendar, administration, contacts, etc.), the Suggestion Box is used to find out our users’ expectations and what improvements can be made given a variety of constraints.

Categorising the Suggestion Box allows us to restrict the analysis of suggestions to the module we have chosen to upgrade.

Bottom line

Two years after the Suggestion Box was launched, feedback is extremely positive.

Today our backlog includes 78 stories broken down into 22 EPIC while previously, we were struggling with 470 stories in backlog and another 170 non-analysed features.

The Suggestion Box includes 224 suggestions, 662 votes have been made on 134 suggestions. 50 suggestions have been carried out, some with many votes (up to 46), some with fewer votes but that were considered high-priority.

Additional Information

You can find BlueMind’s Suggestion Box at https://community.bluemind.net/suggestions/

The Suggestion Box is the result of a lot of in-house discussion and reflection, in particular with Dominique Eav, our quality manager and developer of the Suggestion Box.

And, as we keep updating the Suggestion Box, you’re welcome to create a suggestion for the Suggestion Box!

Enregistrer

Enregistrer