“[…] This crisis teaches us that the strategic importance of certain goods, certain products, certain materials makes European sovereignty a necessity. We must produce more on national soil to reduce our dependency and prepare ourselves for the long term”, Emmanuel Macron declared in his 31 March 2020 speech. Since then, the words “sovereignty” and “independence” have featured prominently in his speeches as well as those of other French government membres.

Although no one questions the importance of being in control of our face masks or medications production, this standard doesn’t seem to apply to digital technology, quite the contrary. Covid-19 has given some businesses and government administrations an opportunity to rush American solutions though, including Microsoft’s.

Has the digital sovereignty everybody was raving about before the health crisis suddenly fallen victim to Covid-19?

“Sovereignty, really, who cares?”

Before the 2020 health crisis, habitual remote work wasn’t overly widespread. According to France Stratégie data (Today’s executives: idiosyncrasies, June 2020), just 3% of workers (including 60% of executives) worked remotely at least one day a week in 2017. Among others, “remote work was an informal, occasional practice: one in seven executives worked remotely a few days or a few half-days a month”.

The health crisis — with many parts of the world in lockdown — has caused an upheaval in the world of remote work and in particular made it more widespread. In France, it is estimated that close to 40% of workers suddenly – and with no time to prepare – had to work from home as of 17 March. Throughout this lockdown period, news articles along the lines of “Top 10 remote work tools” have literally spread like the plague on the internet. There was no getting away (here, here, here, here…).

Although remote work doesn’t seem to be enduring (it dropped back to 15% by the month of August), businesses and government administrations have no intention to give up on the software they started using during that period. Those who had been lured by Teams’ free offering at the height of the crisis are now using it as an excuse to move to O365! Worse still, our clients are telling us “sovereignty, really, who cares?” That’s the irony of the situation, especially when you’re dealing with local authorities that promote local employment and regional economic development! Do as I say, not as I do – technological sovereignty makes the headlines, the highest spheres of the French[SP1] and European governments feign outrage… But in practice, no one really cares and so, why bother?

Well, because above and beyond product lock-in and long-term loss of independence, the negative consequences can quickly become very real: unilateral price increases, expanding scopes leading to ballooning budgets, loss of control on contracts, etc.

Lip service?

As everyone scrambled to set up remote work solutions, practical hiccups were inevitable –employees didn’t have the proper equipment, procedures and tools were confusing or missing altogether. This is when the infamous “Top 10 remote work tools” lists began to sprout. True, after having raved about blockchain and hailed AI as the holy grail that would solve everything (and press releases in particular), a new buzz topic was a welcome change. So what’s the common theme in these articles? Under the guise of the crisis: the promotion of quick-and-dirty solutions – “just install this for your next videoconference, you’ll see it’s great”.

And there goes everyone jumping on the turnkey bandwagon – Zoom, Slack, Teams, Skype, Dropbox, Google Suite… the list goes on! Because these solutions typically offer a free entry point, we all happily dig into the Cloud Act cake like hungry kids at a birthday party. Take a look at Zoom’s 2020 share price:

So, what has become of all the talk about tech sovereignty? Where did the French Senate’s report promoting open European solutions go? What has happened to our standing up to the GAFAMs and forcing them to pay taxes?

Our companies – massively (and dirtily) equipped with American and Chinese technology as they are – are under the thumb of players with overwhelming clout. The TikTok affair is the perfect illustration of how this imbalance of power – on the one hand an app that steals personal data and on the other an executive order that foresees its banning in the US if nothing is done to extract it from its China-based parent company, ByteDance. It’s kill or be killed in the ruthless world of tech giants.

But at the end of the day, the Oracle-Walmart alliance is poised to hit the jackpot. We’re no longer worried the app might spy on us, we know it will.

“There was no alternative”

The reason why everyone has rushed to American/Chinese technologies is that there was no alternative. These giants’ solutions are great – they work well, they are often easy and quick to set up and sold by very effective salespeople with the backing of multi-level lobbying. There is unquestionably a lack of alternatives in some segments.

This is in fact the excuse we most often come across, like in the Health Data Hub controversy regarding the hosting of French health data. According to Bernard Benhamou, general secretary of the French Digital Sovereignty Institute, “this choice also shows some kind of intellectual laziness in the very design of the project whereby we seek to match the GAFAM’s offering without attempting to create an alternative architecture”.

Besides intellectual laziness, this means that people go for the easiest option and short-term comfort despite it being at odds with long-term strategic interests. This is the crux of the issue. This overall laziness amounts to a quick-and-dirty approach – get things sorted out first and think later. We satisfy our brains’ quick reward urges without worrying about long-term effects.

Damn! I’m no longer in control of my data. Shoot! I can’t get out of that contract. Oops! There aren’t any European alternatives anymore! Bugger! I’m out of negotiating power.

We make grand speeches about global strategic visions but our actions are short-sighted. In last May’s address before the Senate about national security and armed forces, Guillaume Poupard, director general of France’s National Agency for Information Systems Security (ANSSI), argued:

“We can’t do everything, but we can continue along the ridgeline that can keep us inside the circle of sovereign countries. But to do this, we must turn our backs on global easy-to-use and easy-to-access — and often cheaper — solutions, at least in the beginning… If, when we built our force de dissuasion, we had chosen the best short-term value for money, we probably wouldn’t have developed all the industries we enjoy today.”

There are European alternatives in many areas. So, what are we missing to make them grow and multiply? Contrary to popular belief among tech reputation-washing circles, there’s no shortage of unicorns – European GAFAMs, local companies that will make a break on the international scene. No, what we are missing a bona fide tech industry policy, a can-do attitude and support from European states and decision-makers. Octave Klaba, CEO of OVH, perfectly summed this up in a 4 July 2020 tweet: “What we are missing is trust in today’s players. You have to encourage them and drive them to innovate in the products needed and then buy them. No one here is looking for subsidies or capital. There’s plenty of money going round already. And business!”

A muzzle on the American ogre?

On 16 July 2020, the European Court of Justice (CJEU) invalidated the “Privacy Shield”, US-based companies’ self-certification mechanism. This mechanism had been approved in 2016 by the European Commission as offering adequate protection for personal data transferred from the EU to the US… and is therefore being invalidated in 2020: “As a consequence of such a degree of interference with the fundamental rights of persons whose data are transferred to that third country, the Court declared the Privacy Shield adequacy Decision invalid.”

In other words, the CJEU believes that US companies’ processing of European data is incompatible with the GDPR. The European Data Protection Board (EDPB) is currently reviewing this decision to assess its consequences .

The EDPB’s FAQs reads: “Transfers on the basis of this legal framework are illegal. Should you wish to keep on transferring data to the US, you would need to check whether you can do so under the conditions laid down below.”

Measuring the extent of these consequences today is impossible. European companies and administrations who use extra-European software publishers out of convenience (or laziness) will have to face up to it regardless. It is crucial that this risk is taken into account when assessing a software solution.

Email, the elephant in the room

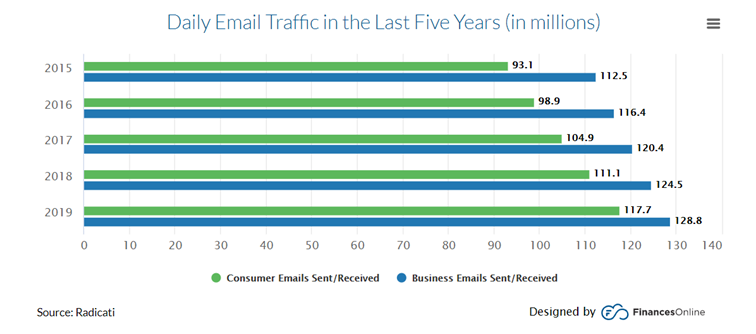

Everything, absolutely everything goes through email. In fact, all the solutions listed in the “top 10 collaborative tools” require an email address to sign up. Email is by far the tool most used in companies on a daily basis, and it is also the most critical. A 2019 Radicati study shows that its usage – both private and business – keeps growing year after year:

The average office worker receives 126 emails a day – with a ratio of 3 emails received for each sent. Inboxes are so demanding that employees report to spend 16% of their weekly work hours to mail-related tasks. 42% of emails are opened on a mobile phone or tablet (source FinancesOnline).

The reason why it is seldom considered as a remote work tool is that it is taken for granted – like oxygen is to breathe. No one will tell you that you need power and an internet connection – it goes without saying.

It is precisely because email is a core tool for all businesses – whatever their activity or size – that it should draw decision makers’ attention. Must we rely massively on Microsoft? Must we put up with Google’s terms and conditions as something inevitable? Especially considering that in that particular instance, there are alternatives!

BlueMind is a European, sustainable, opensource solution that is compatible with all uses – natively Outlook compatible, the best Thunderbird support, excellent mobile and Mac support, a brand-new webmail app, etc.). BlueMind pulls out all the stops to deliver a solution that combines sovereignty and user satisfaction – bringing an alternative to the market and offering a choice.

Conclusion

In a recent article “Digital technologies: the reason France can’t do without the US “(Les Echos, July 2020), the journalist Florian Debes expressed his concern: “just like France was short on surgical masks in March, it is at risk, in the future, of being short on software or the data at the core of its medical research”.

This health crisis just shows that the concept of sovereignty remains too obscure, too abstract. We only take the right measures once the crisis is upon us. Today, health sovereignty has become a priority… at the expense of tech sovereignty. Lockdown has all but accelerated and deepened our dependency on foreign, short-term, quick-and-dirty software solutions.

Fortunately it’s not all doom and gloom. Experts are mulling over European tech sovereignty and many players are joining forces (CNLL, PlayFrance.Digital, l’institut de la Digital Sovereignty Institute, etc.). But understanding and being aware of the issue isn’t enough. It is time to act – to design ambitious policies and support and promote local solutions.

Things are slowly changing at the European level. The Commissioner for the Internal Market Thierry Breton professes that the EU “need[s] better supervision” over tech giants. The EU is expected to release a new law by the end of the year – the “Digital Services Act” – designed to better control how major platforms deploy their activities, deal with disinformation and manage personal data.

Now that the early-lockdown panic-induced dust has settled, it is time to think long term and reflect on the sustainability of the solutions we’ve adopted in a rush. It is unfortunate that many organisations have used the Covid crisis as an excuse to switch to Teams and Microsoft 365.

And in closing, we’d like leave you with a question to reflect on: what kind of technology do we, do you, want?