On 24 June 2020, in the midst of the pandemic, the Town and Country Planning and Sustainable Development Committee delivered its report to the French Senate: “For an ecological digital transformation”. The Committee’s objective was to “measure the environmental footprint of ICTs in France, assess its evolution in the coming years and formulate courses of action for the relevant public policies in order to commit our country to ecological digital transformation, i.e. on a path that is compatible with the objectives of the Paris Agreement to combat global warming.”

Here’s a highlight of the report’s conclusions:

- Greenhouse gas emissions from digital technologies keep increasing – according to the report, on a constant policy basis, they are expected to have grown by more than 60% by 2040, which seems rather optimistic considering other forecasts predicting increases of 9-10%… a year!),

- Digital technologies continue to be largely ignored by environmental policies and aren’t seen as polluting by users,

- Reducing digital technologies’ environmental footprint in France is an act of digital sovereignty. Relocating these activities would help reduce the country’s carbon balance – 80% of France’s carbon emissions being produced abroad.

So, what can we do right now? Can we be pragmatic and optimistic at the same time? (spoiler alert: yes, we can).

Digital technologies: what truly causes pollution

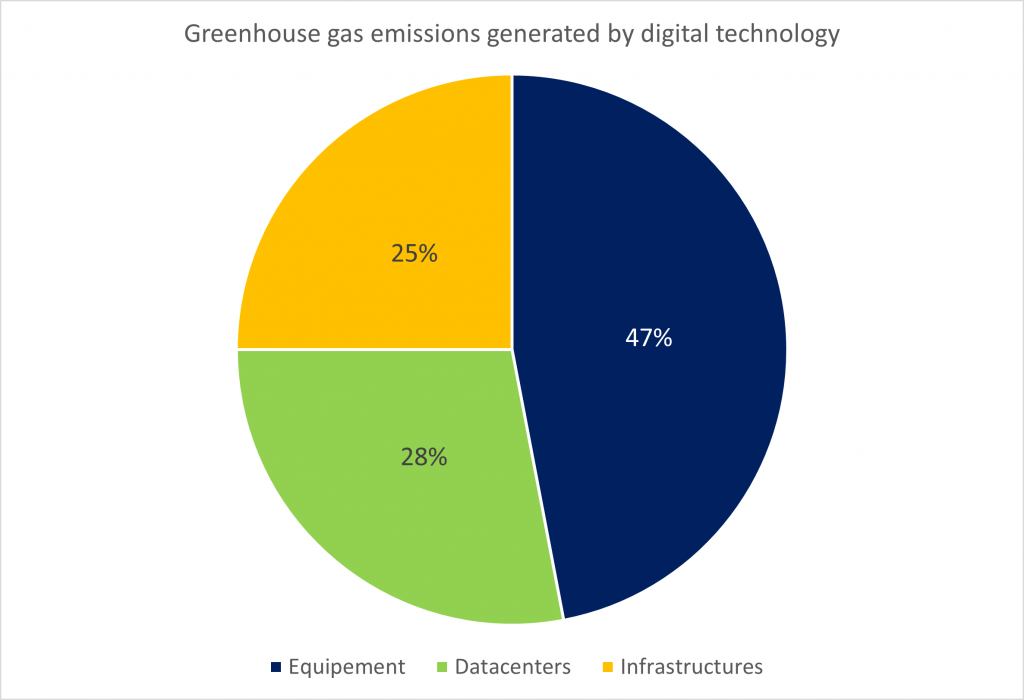

“Most currently available figures show that ICTs accounted for 3.7% of overall greenhouse gas emissions (GHGE) worldwide in 2018, and 4.2% of global primary energy consumption. 44% of this footprint is thought to be caused by the manufacturing of computer terminals, ICT centres and networks and 56% by their use.” (Source: French Senate 2020)

Within five years – between 2015 and 2020 – the amount of electronic waste has grown at three times the rate of human population… Europe holds the dubious title of largest producer of electronic waste per capita, at 16,2kg a year. In Switzerland, for instance, between 1990 and 2005 the average physical mass of a mobile phone has been divided by 4.4 while the global mass of all phones used has increased 8-fold as a result of a boom in the number of users (Sources: GreenIT, EcoInfo and The Global e-Waste Monitor).

Software is all but the tip of the iceberg as its impact tends to be underrated. It does, indeed, significantly contribute to digital pollution, on the one hand because it mobilises datacentres – which, according to ADEME (France’s Environment and Energy Consumption Agency), accounts for 10% of power consumption in France – and on the other hand because it drives the obsolescence of the equipment and infrastructure it relies on.

Legal provisions against software obsolescence

There are several ways obsolescence can sneak itself into software: through limited technical support for older versions, older formats being made incompatible with new versions, discontinued support on the latest operating system versions, forced hardware upgrades, etc. For example, according to greenIT.fr, the Windows 10/Office 2019 combination needs 171 times more RAM than Windows 98/Office 97.

The June 2020 Senate report puts forward a series of measures to help combat software obsolescence:

- Making it compulsory for software publishers to disassociate corrective updates – required for hardware safety purposes – from upgrades – which are not mandatory and can speed up hardware obsolescence.

- Creating a right to reversibility: being able to revert to an earlier version of a software or operating system if an update has caused a device to slow down.

- Restricting the number of applications preinstalled by the vendor on a device or, at a minimum, giving users the possibility to uninstall them.

- Safeguarding the installation of open-source software. Open-source software is less resource-hungry than proprietary software and it can be used on older, less powerful hardware. Unlike proprietary software, its source code is open and can be examined, scrutinised and corrected, which limits intentional obsolescence.

Two European directives (2019/770 and 2019/771) already stipulate the obligation for suppliers to provide updates for a sufficient period of time, but they haven’t been made into French law. In France, planned obsolescence already is a criminal offence, although it is difficult to prove, particularly when it comes to software. Since February 2020, law 2020-105 on Resource Waste and Circular Economy toughens suppliers’ duty of disclosure to consumers for software updates on electronic devices.

The impact of email

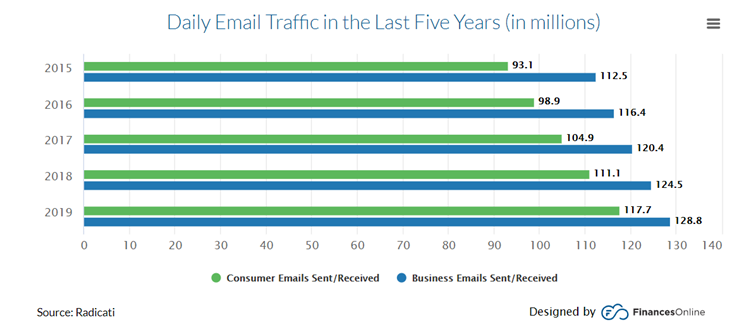

The use of email keeps growing and isn’t showing signs of waning – both in businesses and by the general public:

What is its actual weight in digital pollution? It is difficult to establish precisely, emails themselves don’t cause pollution, but their transit via datacentres does. Some datacentres are more power-hungry than others. And the environmental impact of emails also depends on their size, and figures vary significantly from one study to the next. It is estimated that an email message with a 1Mb attachment accounts for 20 grammes of CO2. While this is small individually, put together it quickly snowballs considering that billions of emails are sent every day.

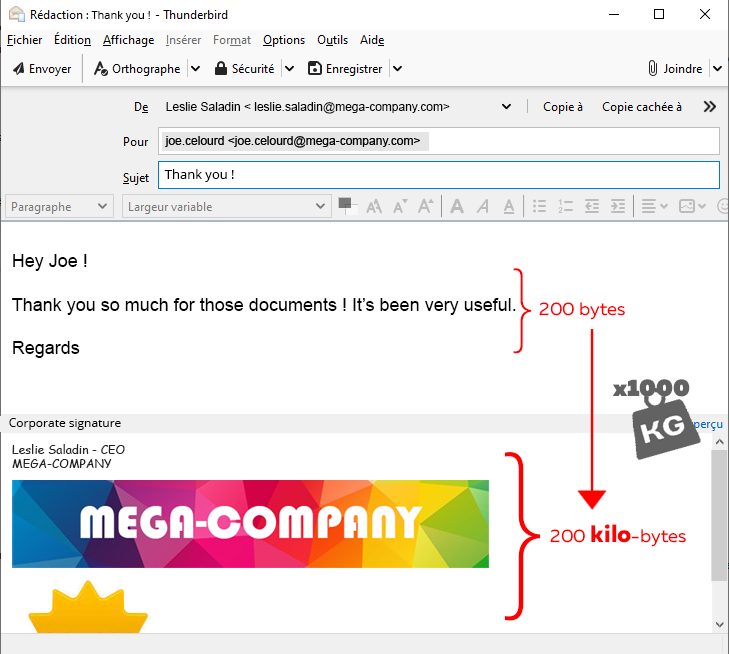

Regrettably, the size of emails is constantly growing. Initially, emails were mere text messages that weighed just a few bytes or kilobytes. With HTML, they have become “rich” and therefore heavier (a few kilobytes or a dozen kilobytes), which remained reasonable. But with images becoming more widespread, emails have become overweight. Signatures now weigh tens, hundreds or even thousands of times more that the message body itself.

But it is also important to consider that 55% to 95% of all email sent every day is spam! And amidst non-spam messages lurks a huge amount of email malpractice, such as using it as a DMS (e.g. keeping messages that contain documents) or as a chat application. Paradoxically, the infamous footer message encouraging you to be environmentally responsible and print only if necessary adds significant weight to the email.

The impact of email on digital pollution is therefore largely due to malpractice. But there are a few good practices you can adopt to limit your inbox’s footprint:

- Optimising attachment size – using low definition, compressing files, adding download links rather than duplicating attachments to multiple recipients, usinglinked attachments (a native BlueMind feature),

- Unsubscribing from superfluous newsletters and distribution lists,

- Sending the message to relevant or essential recipients only (one of our blog articles on improving email productivity addressed this particular issue, as, in addition to being harmful for the environment, CCing too many people also pollutes recipients’ attention),

- Regularly deleting unnecessaryemails and storing their attachments elsewhere. All too often inboxes are used as a DMS, and attached documents are resource-consuming, even when they’re not moving. There are many solutions around to interface with your mail system and help you manage documents, e.g. Jalios or GoFast.

Digital frugality and open source: a way forward?

The tertiarisation of the economy coupled with digital transformation has led to significant changes in the way we work. At every level in the organisation, digital tools are becoming ubiquitous, leading to a 9% increase in tech-related power consumption every year. This pace may be alarming, in particular considering that, for now, the issue continues to be left out of government environmental policies.

To counteract the harmful effects of ICTs and, in contrast, contribute to maximising their positive impact on the environment (because it is possible!), experts recommend adopting a “digitally frugal” approach.

Hugues Ferreboeuf, manager of the “Lean ICT” project at the Shift Project – an ecological transformation think tank – told the Senate in January 2020 that: “frugality doesn’t mean abstinence or degrowth. It means, for instance, reverting to a 15% yearly growth in traffic rather than 25%. We’d still have double-digit growth which should continue to support the digital sector’s economic growth and businesses’ and States’ digital transformation”.

Email is a good example. Between signatures, attachments and images, the actual informational content of the message only accounts for 1% of its total weight! A simple step could be limiting the size of email signatures or deleting them automatically in replies or forwards. This could lessen its impact without hindering growth.

Digital frugality therefore first and foremost aims to raise awareness about the environmental impact of ICTs as dematerialisation and miniaturisation tend to obscure it.

Secondly, digital frugality aims to make digital systems more durable – with longer lasting, more ethical, hardware and software (choice of materials, assembly location, software obsolescence, etc.). In its report, the Shift Project deplores that “professional digital devices are becoming more standardised and the renewal of all the equipment occurs independently of the functional status of each device”.

Open source is particularly relevant within a more frugal use of ICTs, especially thanks to its lean development methods – developing what’s truly useful rather than a whole battery of standard features – and its guiding principles – sharing and collaborating, rather than reinventing the wheel over and over again. Product lifespan, robustness and efficiency are at the core of what we do. Just recently, this blog went on a journey into BlueMind’s software production workshop, giving readers a peek into its ongoing development projects and improvements to its open-source baseware.

Low user-barriers to entry (compatibility, hardware requirements, openness, ease of availability, etc.) are a key part of open-source philosophy and formats as a whole.

Conclusion

“Digital frugality doesn’t mean going back to the salt mines, it just means being aware of how critical this resource [digital technology] is and that it is waning. Being aware of its impact can drive our choices and our uses”, argues Frédéric Bordage founder and moderator of Green IT.

Reducing the environmental impact of ICTs entails a change in perception and behaviour. We must come to terms with the fact that our digital consumption does have an impact. As far as businesses are concerned, fast-evolving European regulations coupled with digital sovereignty issues might help speed up awareness.

Meanwhile, at BlueMind, we fundamentally focus on user experience and developing features that help our clients’ digital frugality: signatures with hyperlinks, signatures for external emails only, linked attachments, file archiving, quotas, etc.).

In a context where remote working tools are increasingly popular, let’s hope that companies’ ICT projects quickly embrace digital frugality – not as a constraint but as a positive prerequisite. Now… #TheChoiceIsHere.

Written with Pierre Baudracco